On Saturday, on the final weekend of the Churches Unlocked Festival we explored the coracled figure of St Columba and other Celtic saints, and asked what their heritage means for us today!

Here, from this coracled figure of St Columba, we hope to take some inspiration, and from the spiritual life he represents, sharing stories, poetry and prayer from the Christian Celtic Tradition, both ancient and contemporary.

But why is St Columba here in the first place? Well, the name and image of St Columba is here at St Saviour’s because the first church of the Established Church in Splott was St Columba’s School Chapel, which stood on the site of the India Centre and was built in 1877.

When St Saviour’s was consecrated in 1888, it was closed for worship though still used as an infant School. It was reopened some years later and had quite a thriving congregation until it was closed in the 1920s. Today the site is still surrounded by Scottish street names because the houses there were built by the Marquess of Bute, and so he brought to Splott his own Scottish heritage. And we can assume that, because of this, the chapel, which was built on land given by him, received the patronage of St Columba, the Apostle to Scotland. As well as the beautiful statue of Columba, modelled on a much smaller statue in the Shrine of Our Lady of Walsingham, he is also present in stained glass, and in the remnants of a chapel here in the south aisle.

St Columba though was Irish and journeyed to Scotland when he was about 40 years old. He settled on the island of Iona from where he evangelized much of the northern and western parts of Scotland. Although both St Ninian (whose name is also well known in Cardiff for the same reasons as Columba) and St Mungo had been active in Scotland before him, Columba deserves the title, ‘Apostle of Scotland.’

He spent some time in the monastery of Clonard overseen by St Finnian. Here he may have experienced something of the traditions of the Welsh Church, for Finnian had been trained in the school of Saint David. Columba was eventually forced to leave Ireland after being on the losing side of a bloody battle in the year 563. We’ll hear more of his journey later.

Tall Tales?

Many stories handed down to us from the Celtic saints of this time appear to be rather extraordinary and extravagant, fanciful and fairly romanticized. It may be difficult to pull fact apart from legend, or to find the truth in the tales, particularly since sometimes their lives may have been written some centuries after their death.

Many of the stories feature amazing miracles, and also reveal an intriguing and intimate relationship with animals and the natural world.

Stories like this, for example, from St Colman of Dromore (County Down, Ireland). In his love of solitude and poverty, he learned much from three strange companions. A cockerel woke him for prayer through the night. A mouse nibbled at his clothes to wake him each morning. And a fly walked down the page to mark the lines of Scripture Colman was reading.

When they eventually died, he was filled with sorrow which he shared with St Columba who replied, “To you, the cockerel, the mouse and the fly were as precious as the richest jewels, so rejoice that God has taken these jewels to himself.”

Sounds fanciful to our modern view of the world? Well, let’s hear from someone a bit more contemporary. Nadeem Aslam, a British-Pakistani novelist, in an interview on Radio 4, said, “Just last month I went for a walk in the hills and there was a beautiful fungus growing on a fallen log so I decided to make a drawing of it. And as I was making a drawing of it, an orange bodied sawfly came and landed on the very tip of my pencil, just a millimetre away from the surface of the paper. And I flicked my hand to make it fly off, but it didn’t. I must have made about two dozen lines and marks and curves, and it stayed there, and then it flew away. And as I was walking away, I asked myself, was that ordinary or was that extraordinary. That is what you need as a writer. You need to be at that level where that boundary between the extraordinary and the ordinary somehow becomes blurred. And you’re not sure if not everything is not a miracle.”

What other miraculous animal tales are there in the Celtic Tradition?

St Piran, like Columba, was born in Ireland. After being tied to a millstone and thrown into the sea by his fellow Irishmen, he was washed up on the shores of Cornwall. There he established his monastery, not at first with monks but with a boar, a fox, a badger, a wolf and a doe. They were his first brothers, as it were, the first members of his community, with whom he built a house of prayer.

St Kevin of Glendalough nurtured a nesting blackbird and her young in the palm of his hand as with outstretched arms he prayed, until they were ready to leave the nest. He also attracted a cow who would escape secretly from the rest of the herd to spend time with him and who, because of these encounters, provided the most profuse and rich milk of all the herd.

And then there is wild boar who took safety in Kevin’s company when being hunted by a cruel huntsman called Brandub who hunted for pleasure, and who took as his victims both human and animal. Following an encounter with St Kevin, both the boar and Brandub were saved!

St Mungo of Glasgow, wandering with his wild hound companion, finally discovered the spot of his new monastery because of the welcome he received from a robin who flew from a tree, perched on his shoulder, and kissed his neck. The site is where Glasgow Cathedral now stands.

Then there are tales of St Cuthbert of Lindisfarne who used to rise in the middle of the night to pray alone. One night, he was secretly followed and watched by one of his brothers. He saw Cuthbert go down into the river and wade out until his arms and neck were covered. There he remained praying for hours. When he emerged onto dry land, he knelt in prayer and otters came up and stretched out beside him, warming his feet with their breath, and drying him with the heat of their bodies.

The life of our own St Cadoc is no different, and features animals as big as boars and tiny as mice. Possibly born at Gelligaer, it was a boar which marked the place for Cadoc to build his oratory at Llancarfan in the Vale of Glamorgan. It was a mouse which led him to a hidden room full of grain during a famine, and stags which were tamed to pull timber for building so that his followers weren’t deterred from their study of Scripture.

St Cadoc played a part in the conversion of St Illtud, and when he escaped from the royal household, and settled in the place we know as Llantwit Major, a stag came bounding into his hut whilst he was praying. A number of hounds arrived after the stag but remained outside. They fell silent with heads bowed. King Paulinus and his knights arrived, ordering them to go in and kill the stag but they remained still. Illtud emerged and welcomed them into his hut to eat. At that moment, the stag poked his head out of the hut and stared at the scene outside. The King’s heart softened, and they crowded into the hut for a meal. Illtud led the stag outside who lay with the hounds in peace. Two of the most famous students of Illtud were St David who evangelised West Wales and St Samson who sailed to Brittany.

A companion of David was St Teilo. In fact they may have been cousins, and they travelled together to Jerusalem along with St Padarn.. When a local lord offered St Teilo all the land he could encircle between sunset and sunrise, he chose to ride on a stag so he could gain as much ground as possible.

So, yes, there are many stories of the Celtic Saints which feature animals, which expresses the close bond between them and all that God has created. Whilst the legendary tales may be difficult to fathom with our modern minds, the stories can captivate us and, if we dig deeper, they can reveal something of the character of the saint and their intricate relationship with everything that exists. They may seem fanciful and far from the truth, but sometimes, to quote Nadeem Aslam, “you’re not sure if not everything is not a miracle.”

Of course, we have shining examples of people outside the Celtic tradition, like Francis and Julian whose spirituality embraced the natural order, but in Celtic Christianity we have a whole church which saw within every living creature the divine spirit, and so loved all creatures for their own sake.

Emerging from these stories is an ancient secret waiting to be discovered in the way we relate to the natural world. They are, perhaps, a call to pause and look at the beautiful miracle of God’s Creation, to see the details we miss so easily in our busy and distracted lives, to marvel in all that God has made, and to show it respect as the richest of jewels which belong to God, and over which we have been set as stewards not masters.

In a more modern poem, by the Welsh priest poet RS Thomas we read:

A message from God

delivered by a bird

at my window, offering friendship.

Listen. Such language!

Who said God was without

speech? Every word an injection

to make me smile. Meet me,

it says, tomorrow, here

at the same time and you will remember

how wonderful today

was: no pain, no worry;

irrelevant the mystery if

unsolved. I gave you the X-ray

eye for you to use, not

to prospect, but to discover

the unmalignancy of love’s

growth. You were a patient, too,

anaesthetised on truth’s table,

with life operating on you

with a green scalpel. Meet me, tomorrow,

I say, and I will sing it all over

Again for you, when you have come to.

Celtic Pilgrims

A particular feature of Celtic mission was pilgrimage. Many, like Columba (shown here in his favoured mode of transport) and St David (whose image is also nearby) had clear plans to convert specific territories but many others set out quite aimlessly, trusting that God would lead them. Often, they found themselves in secluded places, or set out to discover places of isolation, where they could begin to establish a community.

As I mentioned earlier, St Columba was born and brought up in Ireland, and for the first few decades of his ministry he travelled around there establishing monasteries. As he set off from Ireland, travelling east to Scotland across the water in his coracle, his heart was almost breaking for his homeland, poured out in the laments attributed to him. Here are just a few of his laments. (cf Celtic Fire, Robert Van de Weyer, page 31)

Great is the speed of my coracle, its stern turned upon Derry.

Great is the grief in my heart, my face set upon Alba.

My coracle sings on the waves, yet my eyes are filled with tears.

I know God blows me east, yet my heart still pulls me west.

My eyes shall never again feast on the beauty of Eire’s shores

My ears shall never again hear the cries of her tiny babes.

If all Alba were mine, from its centre out to its coast,

I would gladly exchange it for a field in a valley of Durrow or Derry.

Carry westwards my blessing, to Eire carry my love.

Yet carry also my blessing east to the shores of Alba.

Closer to home, St Cadoc regularly pushed out from the mainland of south Wales to the island of Flat Holm for retreats during Lent, accompanied by his companions, Baruch and Gwalches. Meanwhile on the sister island of Steep Holme resided his friend, St Gildas.

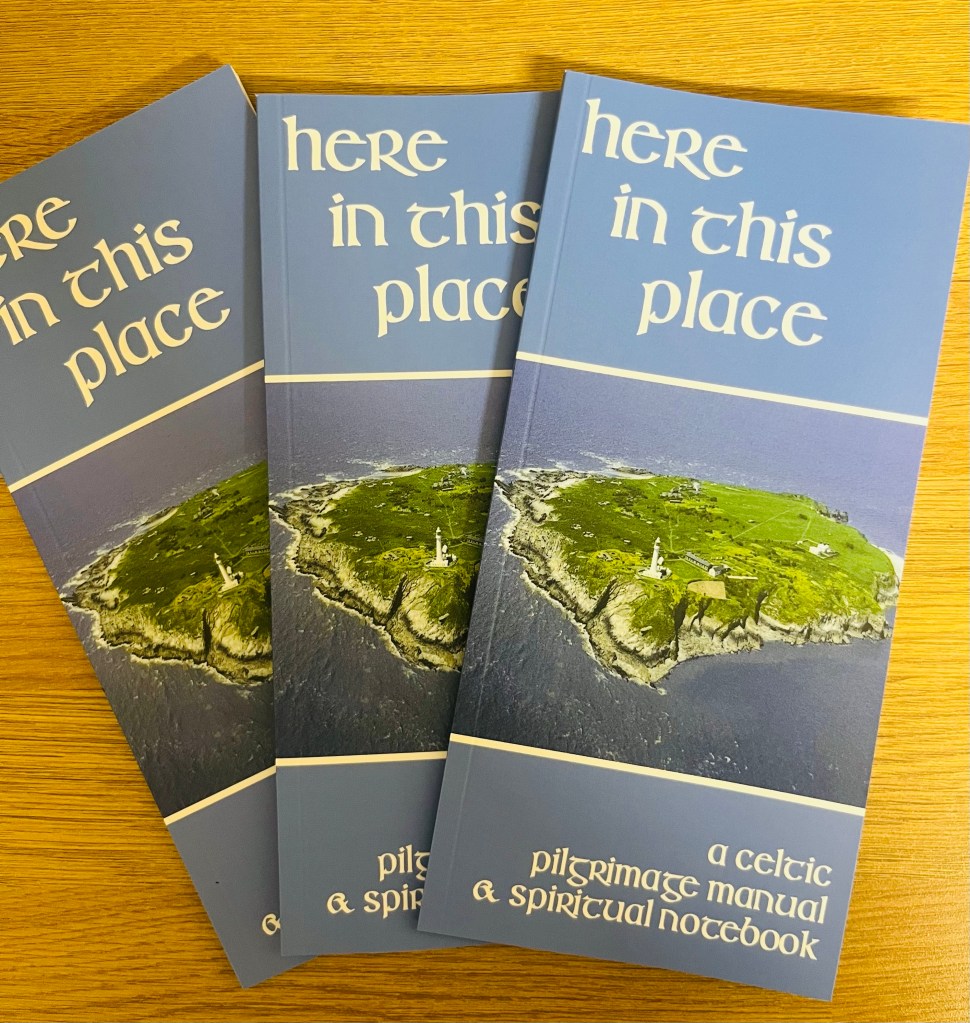

It was on the return of one of these journeys that Cadoc realised an important prayer book had been left behind, so he sent his two companions back, and during their second return journey, the coracle capsized, and each died. Baruch’s body was washed up on the beach to which he gave his name, Barry Island, and Gwalches’ body found its way to Flat Holm. We’ve re-established a pilgrimage programme to Flat Holm, with an accompanying book of prayers which we will use during this time together.

Here’s a prayer featured in our Flat Holm Prayer Book, Here in this Place, called ‘The Crossing: a prayer of God’s presence’:

We journey some distance to be closer to the One who has never left our side. We cross the waters to a lonely place to encounter the One who continually stands before us. We rise and fall across the waves to embrace the One who always holds us. Trinity of Love, you cross boundaries and swoop across the chasms of our lives, enfold us and gather us into your life, Father, Son and Holy Spirit.

Perhaps the greatest pilgrim of Celtic Christianity was St Brendan – who journeyed across the Atlantic from Ireland in a coracle with fourteen of his brothers. After his death, the Latin version of his life was translated onto French, Flemish and Saxon.

He was Abbot of Clonfert, a large monastery in central Ireland. One Lent, he returned to the south-western tip of the country where he had grown up and spent the time on a high mountain, overlooking the ocean. Others had sailed before him in search of what was called ‘The Island of Promise’ and Brendan decided it was time for him to follow. From their descriptions of the places they visited, it’s likely that they sailed a giant circle via the Faroe Islands and Iceland to Newfoundland, returning via the Azores, which they took to the be the Island of Promise.

Whilst there they were there, they encountered a young man who welcomed each brother by name. He then told Brendan to return home to prepare for his final journey, and the wind pushed them onwards back to the shores they had once left.

They were greeted with joy by their brothers, and after recounting their experience and the message of the young man, Brendan prepared for his final journey home to Heaven, and in Brendan’s prayer on the mountain we see him gazing across the eternal sea to heaven, letting go of his life in this world. Here’s a metrical hymn version from our Flat Holm prayer book on Brendan’s Prayer on the Mountain (Tune: O Waly, Waly)

O shall I, King of Mysteries, abandon all for sake of thee? Give up the land which nurtured me and set my face towards the sea? Shall I give up my need of fame, protection, pow’r and wide acclaim? No food or drink to bring delight, no bed to lay my head at night. O shall I say farewell to all, my land, my home, all that enthrals? Pour out my heart, confess my sins, in streaming tears for love of him? O shall I kneel upon this shore my knee prints marking out my prayer? Abandon all and take the wounds believing now that I’ll be found? Shall I push out across the wide expanse of sea and ocean tide? Shall I let go upon the waves and trust alone in him who saves? Across the sparkling seas and storms, O, King of Heav’n, O Christ my Lord, you bid me come to Heaven’s shore. I choose you now, for evermore.

Poetry and Prayer

The spiritual and cultural heart of the Celtic Church were the monasteries – established communities of brothers and sisters, some peopled by both men and women at the same time, and both of whom were able to take positions of leadership. Just think of the likes of Hilda of Whitby and Brigid of Kildare whose monastery was the largest in the whole of Ireland:

“Sit safely, Brigid, on your throne. From the banks of the Liffey, to the coast, you are the princess of our children, ruling with the angels over us” (Celtic Fire, Robert Van de Veyer)

The monasteries created a new Christian community, and the Abbots and Abbesses were the local religious leaders, and through their communities the Christian gospel became part of the tribal and rural culture of the Celtic lands. Some consisted of just a few, no more than ten or twenty, which attracted others, whilst others became were a home to hundred and thousands, from where others then sought more solitude and established more communities.

Every monastery had its scribes who copied the Scriptures and every monk was expected to read and reflect on them. (Some of you may be familiar with the beautiful Lindisfarne gospels which are now housed in Dublin). The Celts though were not renowned for their scholarship. Although there were great schools of learning such as that at Llantwit Major, they preferred expressing their faith in stories and poetry. In the following prayer, we can sense the self-mocking humour at their intellectual efforts in a piece of Celtic verse about ‘The Scholar and his Cat.’ (Robert van de Weyer, Celtic Fire, p74)

I and my white cat has his special work: his mind is on hunting, while mine is on the pursuit of truth.

To me, better than any worldly thing, is to sit reading, penetrating the mysteries of creation. My cat does not envy me, but prefers his own sport.

We are never bored at home, for we each have endless enjoyment in our own activities, exercising our skills to the utmost.

Sometimes, after a desperate struggle, he catches a mouse in his mouth; as for me, I may catch some difficult law, hard to comprehend, in my mind.

He enjoys darting around, striving to stick his claw into a mouse; I am happy striving to grasp some complex idea.

So long as we live in this way, neither disturbs the other; each of us loves his word, enjoying it all alone.

The task which he performs is the one for which he was created; and I am competent at my tasks, bringing darkness to light.

Celtic Christians lived out their faith during each day, marking each moment with prayer, aware of the closeness of God, from morning to night and through the night.

There are prayers on rising and going to rest, when kindling the fire or before eating, prayer on the passing of time, and on the shortness of life, but they did not live in fear of death. Rather they embraced it as part of God’s designs. Their prayers are filled with images from nature, and those which reflect the changing seasons of the year. There are prayers like St Patrick’s Breastplate which is both a prayer for protection and a prayer of intimacy, of putting on Christ, of Christ being close, which we know well in this metrical version:

Be thou my vision, O Lord of my heart;

naught be all else to me, save that thou art.

Thou my best thought, by day or by night,

waking or sleeping, thy presence my light.

Be thou my wisdom, be thou my true word;

I ever with thee, and thou with me, Lord.

Born of thy love, thy child may I be,

thou in me dwelling and I one with thee.

Be thou my buckler, my sword for the fight.

Be thou my dignity, thou my delight,

thou my soul’s shelter, thou my high tow’r.

Raise thou me heav’nward, O Pow’r of my pow’r.

Riches I heed not, nor vain empty praise;

thou mine inheritance, now and always.

Thou and thou only, first in my heart,

Ruler of heaven, my treasure thou art.

True Light of heaven, when vict’ry is won

may I reach heaven’s joys, O bright heav’n’s Sun!

Heart of my heart, whatever befall,

still be thou my vision, O Ruler of all.

In our Flat Holm book, we have similar prayers and also prayers on leaving the house or prayers when travelling. Each moment is or can be a sacred one. Here’s one such prayer which rejoices in the presence of God in his Creation, called ‘A New Creation: A Prayer of the Incarnation.’

God loves material things, the matter of creation. Every atom glows with glory, each fibre is a festival of his power to create. The hidden roots beneath the soil, the microscopic creatures unseen by the human eye - each, in its own minute world, and, in its own tiny way playing its part in the pulse and the breath of the planet. Into this world, among Creation’s matter, leapt God’s almighty Word, first spoken in the beginning, now made flesh and blood in Mary’s own. Their hearts beat in time, a synchronised symphony of love, a beating drum, the breath and play of the planet brought to silence as it awaits the first indecipherable cry of the Newborn who has come to announce a new creation, redeemed by love.

And I love this prayer from ancient Celtic literature reflecting on ‘Youth and Age’ (featured in Celtic Fire by Robert Van de Weyer)

Once my hair was shining yellow, falling in long ringlets round my brow; now it is grey and sparse, all lustre gone.

Once as I walked along the lane girl’s heads would turn to look at me; now no woman looks my way, no heart races as I approach.

Once my body was filled with desire, and I had energy to satisfy my every want; now desire has grown dim, I have no energy to satisfy even the few desires that remain.

Yet I would rather chilly age than hot youth; I would rather know that God is near, than have no thought of him in my head.

I have had my day on earth; now I look to eternity in heaven.’

Celtic Christianity Today

The year 597 was a turning point for Celtic Christianity. It saw the death of Columba in Iona and the arrival of St Augustine, sent by the Pope, in Canterbury. The Celtic church had steadfastly rejected the authority of Rome but now it would begin to accede although not after putting up an obstinate resistance, and slowly the Celtic Church, which had been far more generous in wanting to learn from Rome than the other way around, would begin to lose its grip, and this was cemented in the Synod of Whitby in the year 664

However, the Celtic expression of faith is still retained today. There are still remnants in the lives and outlook of Celtic Christians today both in our love of story and song, in the poetry and prayer, in the Cynefin, our connection to the landscape and sense of belonging, even our stubborn love of gardening and, in Wales, to that sense of Hiraeth and Hwyl, where people express their faith from the heart before the intellect.

What would a modern Celtic Christian spiritual experience or outlook on the world look, or feel like?

1.

One that is intricately woven into the fabric of our lives and believes that God is not separate from his creation, and that there is no moment where, no matter in which he is not. This means not just our experience of nature but the very means of human existence, both rural and urban, and gives us permission to be concerned about all areas of life, as we seek justice for creation and for all human lives.

2.

It would mean a life in which our day is punctuated by prayer, and in which every activity has the potential to be a divine encounter, so that even work is not seen as a distraction to prayer but as a means of prayer. How would that outlook improve our attitude to work, so that we do not simply feel like cogs in the wheel, going through the motions but are participating in the creativity of God.

3.

It would mean being a pilgrim people who pushed out in faith, sometimes across unknown waters in search of that Island of Promise, and so being adventurous and bold., whilst – on the journey – creating community which also embraced seclusion, and the ability to be at home with ourselves and with God.

4.

Finally, at the heart of the Celtic monastery was the constant fire, the hearth that burned. And so to have authentic Celtic Spiritual expression in our own day would be valuing that which gathers and warms us, that which is of benefit to all, each of us fanning the flame, knowing that it is not simply me or you or I who receive the warmth and the benefits, but all.

The End

So, since we started with St Columba let us end with him, and with his own ending to this life and the account of his death which, in typical Celtic tradition features a horse!

Columba was growing weary with age. After visiting some of his brethren on the western side of the island of Iona to say farewell, followed by blessing the granary and the ample heap of grain which comforted him in the knowledge that his brethren would be well provided for, he set back towards the monastery. Halfway along the road, he sat down where a cross had been erected. As he rested, the white horse which carried the milk churns came up to him. The horse laid its head upon Columba’s breast and began to whinny, and even to weep and foam at the mouth. Diormit, Columba’s beloved attendant, began to drive the horse away but Columba stopped him. He said, “Let him alone, for he loves me. Let him pour out his tears of grief here in my bosom. You, a man with rational soul, can know nothing about my departure except what I tell you. But this dumb creature, possessing no reason, has been told by the Creator himself that I am about to leave him.” So, he blessed his servant the horse; and the horse turned sadly way.

Columba later died, lying in front of the altar with his attendant Diormit lifting his right hand to bless the monks. And the whole church resounded with cries of grief. He died on 9 June in the year 597.

The following well known hymn is attributed to St Columba:

Alone with none but thee, my God,

I journey on my way:

what need I fear when thou art near,

O King of night and day?

more safe am I within thy hand

than if a host should round me stand.

My destined time is known to thee,

and death will keep his hour;

did warriors strong around me throng,

they could not stay his power:

No walls of stone can man defend

when thou thy messenger dost send.

My life I yield to thy decree,

and bow to thy control

in peaceful calm, for from thine arm

no power can wrest my soul:

could earthly omens e’er appal

a man that heeds the heavenly call?

The child of God can fear no ill,

his chosen, dread no foe;

we leave our fate with thee, and wait

thy bidding when to go:

’tis not from chance our comfort springs,

thou art our trust, O King of kings.